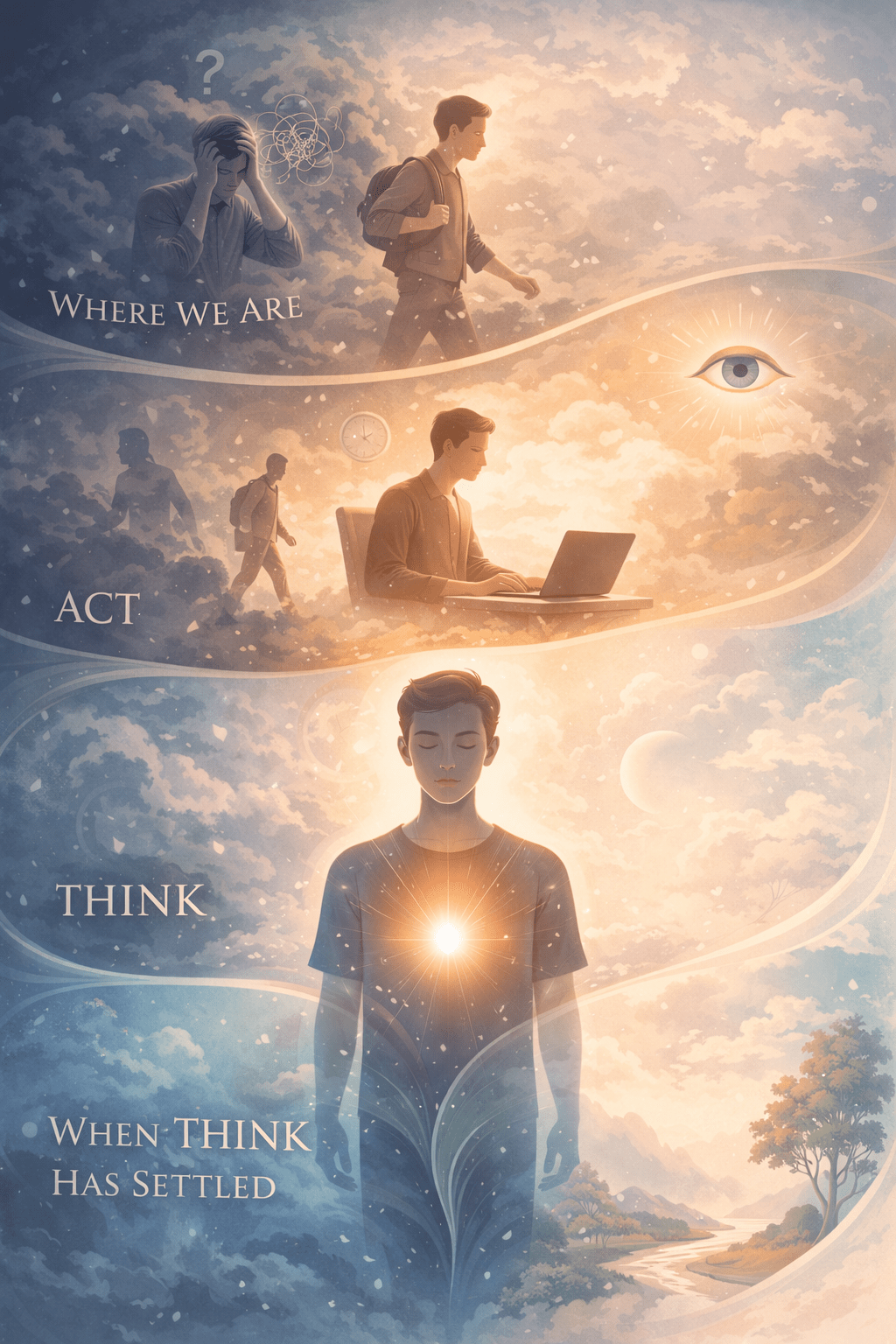

Where We Are

Most of us lead busy lives. Our days are filled with professional work, family responsibilities, and many small obligations. While we complete many tasks, one thing often remains missing: clarity. There is little clarity about how we are actually living. As we observed in “Where Are We? – A Mid-life Introspection,” we rarely look at what our actions are doing to our habits and attitudes. Even after a full day, our understanding of ourselves remains largely unchanged. This recognition points to a simple need. It is not that life lacks activity; it is that our activity rarely deepens our understanding of ourselves.

First Movement from Where We Are

The first response to this condition is to return to life more consciously. In the journey we have mapped out in “The Fourfold Path: Act, Think, Question, Seek,” this first movement is simply to ACT. As discussed in “ACT – The First Step on the Fourfold Path,” this refers to choosing deliberate participation over drift. It means attending to what needs to be done and taking responsibility for the duties that stand clearly before us. By responding with awareness, we step out of automatic living. We re-enter direct contact with our situations as they are, not as we imagine them to be.

This first step of ‘ACT’ brings us back into contact with life, but it does not reveal the “dents of impressions” that we are creating. And so, we may not notice that our repeated actions are hardening into rigid habits. These habits could be a recurring irritation with certain things or a way of avoiding certain people. While acting with responsibility reconnects us with life, we can see that something more is necessary. We need to understand how our daily efforts are quietly shaping our inner character. This is where the next phase referred as THINK comes in.

THINK – The Second Movement

Thinking, in this context, does not mean stopping to analyse things deeply. It is simply a quality of staying awake to our act while we are performing it. It allows us to notice what moves us and how we engage. This awareness does not interrupt our activity; instead, it travels alongside the action. A task that might otherwise be mechanical becomes thoughtful simply because we are present within it.

We notice that when our understanding has a single, clear focus, our effort becomes steady. Without this focus, our energy is easily pulled away by multiple distractions or wayward thoughts. We find this practical observation reinforced in the Bhagavad Gita, which points to the value of a focused resolve as the key to directed effort (vyavasāyātmikā buddhir ekeha; 2.41). A brief gist of Sankhya Yoga would show that, this one-pointedness is what allows the intellect to remain steady amidst the chaos of multiple desires.

THINK as Reflection Alongside Action

Since we are always performing some action, the quality of attention we bring to it is vital. This is where THINK takes the form of an internal reflection. This reflection does not replace our work; rather, it functions as a quiet companion to our effort. Through this practice, it becomes possible to notice our habitual ways of responding to situations. One way this appears is as an awareness of our motive. Even as we act out of sincere responsibility, we can observe when we are being pushed by a personal like or pulled away by a dislike (arāga-dveṣataḥ kṛtam; 18.23). By simply noticing these internal pushes and pulls, we gain the freedom to stay focused on the task itself rather than being driven by these preferences.

Reflection also appears as a certain “presence of mind” while we are busy. We may notice that much of our fatigue actually comes from the friction of worrying about what comes next. When our attention stays with the work, the mental noise of being “somewhere else” or “what happens next” begins to fade. By recognizing that we can manage only this presence of mind and the quality of our effort, the pressure of the future stops weighing us down. Our work becomes steadier because it is no longer burdened by the need to control things like results and future outcomes, which are beyond our reach. The Gita refers to this composed awareness as skill in action and reminds us that our authority is limited to doing the work alone (yogaḥ karmasu kauśalam; 2.50 — karmaṇy evādhikāras te; 2.47). Gita elaborates on this through Karma Yoga too.

We are very likely to see for ourselves that, our actions tend to become meaningful only when we allow the experience to settle into clarity. Rather than rushing to the next task, we must allow the current effort to mature into an insight. This natural completion of action through understanding can be seen as a key theme in the fourth chapter of the Gita (sarvaṁ karmākhilaṁ ; 4.33). Further insight into the full verse, as seen through the gist of Chapter-4, would give a bigger picture.

THINK and the Mind as Its Instrument

Our traditions often describe the mind as an instrument. When the mind is left unattended, our effort becomes fragmented and tiring. This quality of thinking — this sustained awareness of the task at hand — is what keeps this instrument steady. It does not make us slower; rather, it removes the internal rush that creates a sense of chaos.

As this steadiness grows, our very perception of work begins to change. We no longer feel as though we are pushing against a difficult task or clinging to a pleasant one. Instead, the effort, the actor, and the goal begin to merge into a single, smooth movement. We find ourselves in a state where the work is performed with a natural, quiet momentum.

The Gita points to this vision of unity. It speaks of action performed with an inner sense of wholeness, where the act and the actor are seen as one (brahmārpaṇaṁ brahma havir; 4.24). This process, where the effort matures into insight, is the essence of the “Sacrifice of Knowledge” brought out through Jnana Yoga. Sri Ramana Maharshi makes a similar observation in Upadeśa Sāram. He notes that action performed with this sense of offering — placing the effort above our personal desire for results — purifies the mind (īśvarārpitaṁ necchayā kṛtaṁ; verse 3). By treating the work as an offering rather than a means to drive towards a specific personal end, we stay connected to the action itself, keeping the focus firmly on awareness lived through work — not before, not later.

THINK: Its effect on our daily lives

This reflective movement gradually settles into a steady rhythm in our daily life. It begins as a conscious pause before we speak or act but soon becomes a natural awareness that stays with us even while our hands are busy. At this stage, we are not merely managing the task; we begin to observe the way we perform it. When the day’s efforts settle into clarity at the level of the mind, we can sense whether our actions carried a quality of presence or whether we were still being moved by the momentum of the day. This subtle shift ensures that our responsibilities do not harden back into automatic habits but remain as opportunities — opportunities for constant learning for the mind, enhanced quality of work at the body level, and, overall, a more joyous way of living as life moves.

When THINK Has Settled

As this habit of awareness becomes steadier, the focus shifts from the work itself to our inner landscape. We begin to recognize our “default settings” — the automatic reactions and deep‑seated preferences that once remained unnoticed. We might begin to notice a defensiveness that used to appear in our conversations or a subtle impatience to rush through the chores.

Through this sustained observation, the friction that existed between our impulsive thoughts and the thinking process begins to smooth out. The mind is no longer a source of reactive noise; it becomes a refined instrument of clarity. We have now fully climbed the second stage of the fourfold path, transforming how we carry ourselves through every effort.

Over a period of time, this very clarity reveals a new depth in our journey. We reach a point where simple reflection on the quality of our actions becomes a stepping stone toward deeper inquiry. We begin to sense questions about the nature of the “doer” and the purpose behind the effort — questions that reflection alone cannot answer. Having lived the movement of Think to its maturity, we are now ready for the next phase of our journey.